This will probably be the last post here for the DITA module, although I hope to keep the posts going post-DITA too. I thought I’d use this one to address some semantics. Last week’s lecture was about the semantic web and initially I thought it might be a good idea to lay down in my own words, and in as concise a way as possible, what is meant by some of the terms we looked at. There were quite a lot and as I went on I ended up adding things encountered in previous lectures as well. Most of these were jotted down on a piece of paper on a long train journey on Sunday, and while I haven’t generally (apart from one) directly referenced any other sources below, they will inevitably be a paraphrase of the words of others [at least I hope they are paraphrased and not the exact words of anyone – apologies if so] – not least Ernesto, our DITA lecturer, and David and Lyn our LISF lecturers. The definitions are maybe not overly objective – more Samuel Johnson than the OED in places. They may also be wrong… please feel free to disagree, question, or correct anything here.

A DITA Dictionary

Semantic Web – The idea of the semantic web perhaps reflects the structure/process of human knowledge, where meaning exists in terms of a relationship between one thing and another. It is an idea not yet (fully) realised. One way the idea might be realised is by tagging: defining possible relationships in a machine-readable format. BUT while there are some agreed objective connections between things, there are many more (infinitely more?) personal ones, or domain specific ones, or cultural ones, etc… – all of which may agree with, or disagree with, or contradict the others. Can a system of human-imposed tagging ever hope to deal with, let alone replicate, the complexity of this?

XML – eXtensible Markup Language. A loose set of agreed conventions for tagging (/describing) content of a given text in a way that machines can read (although it is often readable to humans too). It can be, and is, modified to different needs and subject specific vocabularies. Its rules, once set up, must be observed (most importantly closing all tags with a ‘/’ – i.e. <name> Carol Channing </name>).

HTML – HyperText Markup Language. A set of agreed conventions for describing format in a web-published document, designed to be read and reinterpreted by a given web browser. It is a bit less strict than the XML rules (you don’t need to close opened tags).

The World Wide Web – Tim Berners-Lee’s concept for a connected web of knowledge, based on the internet and hypertext.

Web 1.0 – vanilla flavoured web. Static documents, albeit connected by hyperlinks.

Web 2.0 – a living web of information, allowing user interaction with and generation of content.

Web 3.0 – the future? the semantic web is sometimes called Web 3.0, and sometimes Web 3.0 is thought to be the ‘semantic web’.

Web Service – cheating on this one – definition from W3C:

“a software system designed to support interoperable machine-to-machine interaction over a network.”

…Twitter and Facebook are examples.

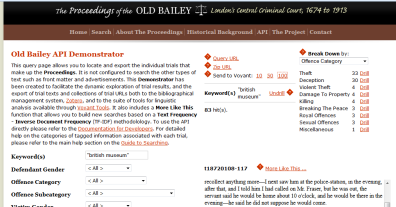

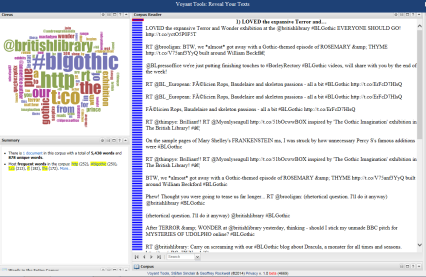

API – Application Programming Interface. Something that allows access to the data within a given system (Twitter, for example), in a way that doesn’t require extensive technical knowledge.

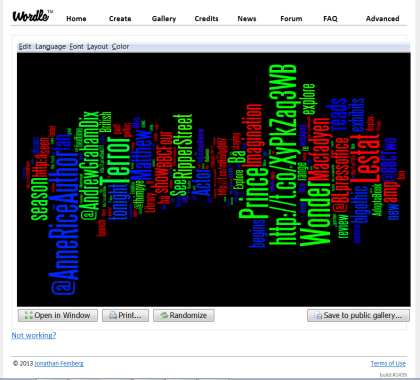

Altmetrics – ‘alternative metrics’. Metrics are measurements which within an academic research context are usually of ‘impact’. Traditionally this might have been a measurement of the citations an article receives. Alternatively, this could be done as a measurement of impact across a wider scope – ‘mentions’ (i.e. an embedded link) in tweets, for example.

Distant Reading – Franco Moretti’s idea of analysing a broad corpus of works to draw more contextual conclusions than are traditionally drawn from the ‘close reading’ of individual, usually ‘canonic’, works.

Ontology – the overriding rules that govern a given system (slightly different to philosophical use).

Taxonomy – an instance of an ontology. The words, categories and classifications to be used to describe and order things in a hierarchy.

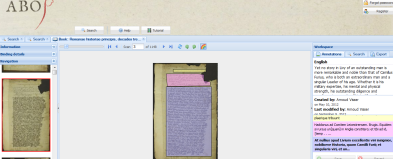

Data Mining – digging for, and extracting, data from something that doesn’t readily present it otherwise.

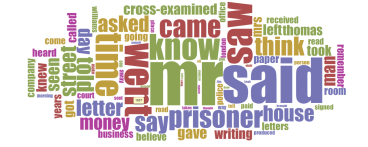

Text Analysis – a form of data mining. Take a body of text and see what quantitative conclusions can be drawn from it.

Information Architecture – information requires structure, and different structures in different situations. The design of this structure is the architecture.

Databases – places to store data in a retrievable and usable way. Relational databases allow connections between related data of differing types.

There are a few I’ve missed out here, particularly more technical things (RDF, URI, XML Schema, JAVA, JSON, OWL spring to mind). I think I need to think about these a bit more myself – and there are neat enough summaries on Wikipedia anyway. In conclusion though I thought I’d have a go at the seemingly ‘must-do’ definitions within LIS – the classic Information-Knowledge-Data-Document set. Once again, these are strongly influenced by reading and lectures, but particularly Luciano Floridi, Lyn Robinson, David Bawden, Ernesto Priego and Tim Berners Lee.

Information – an interpretation of knowledge, translated into a given communication system (words, sound, code, etc.) for the purposes of transferring something from A (that knows it), to B (that doesn’t).

Knowledge – meaning and understanding. Created through having interpreted information presented by an external source, and then connected to existing knowledge.

Data – unprocessed things that have been collected and are awaiting meaning.

Document – a record of information. What can be defined as a document will vary depending on the context of encountering it.